In this article, we will take look at how you can use and configure log4rs to log to a file in your Rust program. Specifically, we will look at some of the options using YAML to configure the logging.

What is log4rs

From the crate description: “log4rs is a highly configurable logging framework modeled after Java’s Logback and log4j libraries.” For the log4rs crate’s page click here.

Why log4rs

What is good about log4rs? It offers an easy way to log to a file and it is highly configurable using a YAML config file, as well as through code. However, in this article, we will focus on using a YAML file to do the configuration.

Log4rs core concepts

There are a few concepts that we need to be familiar with to understand how to build up the configuration file, there are only a few used in basic logging. With this in mind, the concepts we will look at are log levels, encoders, appenders, and loggers.

Log levels

The common log levels are available:

- trace

- debug

- info

- warn

- error

When setting a logger to a certain level it allows all levels above it to be logged as well.

Writing log messages is done using macros: trace!(), debug!(), info!(), warn!(), error!().

Encoders

We use encoders to configure the formatting of the output. The following encoders are available:

- pattern: A simple pattern-based encoder.

- json: An encoder which writes a JSON object.

- writer: Implementations of the

encode::Writetrait.

We will only look at the pattern encoder in this article.

With the pattern encoder, we can format the log entry to not only contain the message we want to log but also additional information. For example, we can add a timestamp. Go to the documentation for more details on patterns here.

Appenders

The output channels are called “Appenders” in log4rs. The output types, or “kinds” are:

- console: writes logging to stdout

- file: writes logging to file, that grows indefinitely

- rolling file: write logging to file. We have options to control max size of the file and whether or not old log files are archived, etc.

There are crates that add other output types for example log4rs-syslog, to log to syslog.

Loggers

A logger is a named logging entity. Therefore, log events can be targeted at specific loggers that are defined by string names. These loggers can override the root logging configuration. However, it is not necessary to configure a logger, you can either configure the root logger, a specific logger, or both of course. For instance, macros debug!(), info!(), etc. will log to root by default.

Logging examples

In this section, let’s look at a couple of logging examples in practice.

Let’s create a new project cargo new log4rs-logging-example. Then add the relevant dependencies to Cargo.toml:

[package] name = "logging-to-file" version = "0.1.0" edition = "2018" # See more keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html [dependencies] log = "0.4" log4rs = "1"

Basic stdout logging

First, a very simple example to log to the console/terminal.

Basic stdout config file

Create a log file in the root of the project, called logging_config.yaml and add the following lines:

appenders:

my_stdout:

kind: console

encoder:

pattern: "{h({d(%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S)(utc)} - {l}: {m}{n})}"

root:

level: debug

appenders:

- my_stdout

The above code listing is showing that the appender, my_stdout, is defined. The appender name can be any string. The kind specifies the output type, in this case, console, which will write to stdout.

We have an encoder that specifies a pattern that indicates what each log line should contain. There are a lot of things going on here, let’s look at the meaning of the symbols:

{h()}: will highlight every text that is within the angle brackets(). The color that log4rs will is using depends on the log level.{d()}: insert a formatted data time string into the message. Adding(utc)at the end there shows the time in UTC.{l}: prints the debugging level for this message.{m}: is the location of the message we intend to log.{n}: is a new line.

A message “test” logged using the “info” level on 2021-08-25 15:19:22 with this pattern will look like:

2021-08-25 13:19:22 - INFO: test

Finally, we have the root configuration. As mentioned before, this configures the default loggers: which appenders are used and what the lowest debug level is.

Basic stdout code

Next, we will look at the code to load this configuration file, and how to log messages.

In main.rs add the following code:

use log::{debug, error, info, trace, warn};

use log4rs;

fn main() {

log4rs::init_file("logging_config.yaml", Default::default()).unwrap();

trace!("detailed tracing info");

debug!("debug info");

info!("relevant general info");

warn!("warning this program doesn't do much");

error!("error message here");

}

On line 5, we are reading in the configuration YAML and the rest of the lines are macros to invoke logging for the respective log levels.

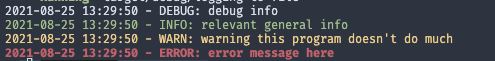

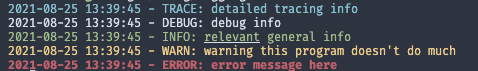

The output will look like this:

Notice that the message logged with trace!() is not shown. This is because we configured the logging level to be debug and above. The trace level is lower than debug so is not shown. If we change the level in the configuration under root to trace, it will be shown.

This is nice for basic logging but for a serious program, we want to learn how to use log4rs to log to a file in Rust.

Basic file logging

In this section, we will create a configuration for logging to a file.

Basic file logging configuration

We are going to update our logging configuration file with new lines for logging to a file:

appenders:

my_stdout:

kind: console

encoder:

pattern: "{h({d(%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S)(utc)} - {l}: {m}{n})}"

my_file_logger:

kind: file

path: "log/my.log"

encoder:

pattern: "{d(%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S)(utc)} - {h({l})}: {m}{n}"

root:

level: trace

appenders:

- my_stdout

- my_file_logger

We added a new appender to the list of appenders called my_file_logger. The kind is file, this requires a path to be configured. Log4rs creates the path and the file if they do not exist already. The encoder and pattern are the same as with my_stdout.

Once we add this appender to the appenders list under root, the logs will be written to the file when we run the program.

With this configuration, log4rs will log to both stdout and to the file we specified. As mentioned in an earlier section, the log file will keep growing. Every time we log a message, log4rs adds it to the same log file and the log file keeps growing. To prevent the machine running our program to run out of disk space due to a giant log file that keeps getting bigger we can use rolling file logging.

Rolling file logging

The next step for better logging is to make sure our files don’t take up all the space on our machine.

Let’s add some code to better test the rolling file configuration, add the following on line 12:

for i in 0..250 {

info!("To test rolling file configurations we print this message in a loop. This is loop nr. {}", i);

}

Every time we run the program now, the log file will grow by about 28kb in disk size. That isn’t much, of course, but, let’s say we don’t want a log file larger than 50kb. We configure this using a different kind of appender:

appenders:

my_stdout:

kind: console

encoder:

pattern: "{h({d(%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S)(utc)} - {l}: {m}{n})}"

my_file_logger:

kind: rolling_file

path: "log/my.log"

encoder:

pattern: "{d(%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S)(utc)} - {h({l})}: {m}{n}"

policy:

trigger:

kind: size

limit: 50kb

roller:

kind: delete

root:

level: trace

appenders:

- my_stdout

- my_file_logger

The updated lines are highlighted. As mentioned the kind for my_file_logger was changed to rolling_file, and a policy section was added to configure the rules for the rolling file mechanism. In this case, the trigger is on a size of 50kb and the roller kind is delete. Meaning, that every time the log file reaches 50kb in size or above, log4rs deletes the file and creates a new one.

This is a fine strategy for keeping the logs clean and current. However, there are scenarios where you might want to look further back for debugging purposes.

Rolling file logging with fixed window

The final lesson we learn on how to log to a file in Rust with log4rs is, rolling file logging with a fixed window. If we configure the roller kind to be fixed_window instead of delete we can keep old log files around:

appenders:

my_stdout:

kind: console

encoder:

pattern: "{h({d(%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S)(utc)} - {l}: {m}{n})}"

my_file_logger:

kind: rolling_file

path: "log/my.log"

encoder:

pattern: "{d(%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S)(utc)} - {h({l})}: {m}{n}"

policy:

trigger:

kind: size

limit: 50kb

roller:

kind: fixed_window

base: 1

count: 10

pattern: "log/my{}.log"

root:

level: trace

appenders:

- my_stdout

- my_file_logger

I have highlighted the changed lines. Here the base determines the starting number, and count determines the maximum number of files. The pattern tells log4rs what the file should be named and where the number should go.

With this configuration, log4rs will log to my.log and if that file exceeds 50kb in size, log4rs will move the older lines to an archive file log/my1.log and then add the new lines to my.log. Log4rs will do this up to my10.log, the higher the number the older the logging lines will be.

Try running the program multiple times and see the effects of this configuration.

Logging to multiple files using loggers

We have yet to use the “loggers” concept that was mentioned in the “log4rs core concepts” section. This is a useful mechanism, to, for example, isolate a special event and log it to a specific file. So let’s look at an example now.

We will update the configuration YAML logging_config.yaml once again:

appenders:

my_stdout:

kind: console

encoder:

pattern: "{h({d(%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S)(utc)} - {l}: {m}{n})}"

my_file_logger:

kind: rolling_file

path: "log/my.log"

encoder:

pattern: "{d(%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S)(utc)} - {h({l})}: {m}{n}"

policy:

trigger:

kind: size

limit: 50kb

roller:

kind: fixed_window

base: 1

count: 10

pattern: "log/my{}.log"

my_special_file_logger:

kind: rolling_file

path: "log/my_special.log"

encoder:

pattern: "{d(%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S)(utc)} - {h({l})}: {m}{n}"

policy:

trigger:

kind: size

limit: 50kb

roller:

kind: delete

root:

level: trace

appenders:

- my_stdout

- my_file_logger

loggers:

special:

level: info

appenders:

- my_special_file_logger

additive: false

The highlights, show the added lines. We have added a new appender config which is set to log to the file log/my_special.log. Furthermore, this file will be deleted and start fresh once it reaches 50kb.

Notice that this appender has not been added to the root section. This means messages will by default not be logged using this appender. At the bottom of the configuration file, we added a loggers section and called the logger special. In the code, this name is used to target that particular logger.

On the last line, we have additive: false this means that appenders of the parent should not be associated with this logger. The parent in this case is root and the appenders are my_stdout and my_file_logger. That is to say, setting additive to true will send the messages targetted at special to those two appenders as well.

The way to target a logger in code is for example: info!(target: "<logger name>", "<log message>");. So, let’s add a line like this to our main.rs file:

use log::{debug, error, info, trace, warn};

use log4rs;

fn main() {

log4rs::init_file("logging_config.yaml", Default::default()).unwrap();

trace!("detailed tracing info");

debug!("debug info");

info!("relevant general info");

warn!("warning this program doesn't do much");

error!("error message here");

for i in 0..250 {

info!("To test rolling file configurations we print this message in a loop. This is loop nr. {}", i);

}

info!(target: "special", "this is info for a special event");

}

After running the project now, notice that our new log message does not appear in the terminal. However, a new log file has appeared in the log directory called my_special.log containing our new log message.

Conclusion

We have a good grasp of how to log to a file in Rust with log4rs. So now, we can log to stdout and to a file. On top of that, we learned how to prevent our machine from running out of disk space from the log files. Finally, we made use of loggers to put certain log messages in a separate log file.

Now we can use this knowledge to our advantage in our other projects. For example, it would be a great addition to our crypto triangle arbitrage dashboard backend project or a WebSocket backend project in general.

Coming from a Java/Scala background, this is an excellent article on how to use a configurable real world logger. Thanks!